The State Law That Governs Local Planning and Development in North Carolina

A plain-language look at how zoning, development approvals, and land-use decisions are regulated under NC State General Statute Chapter 160D.

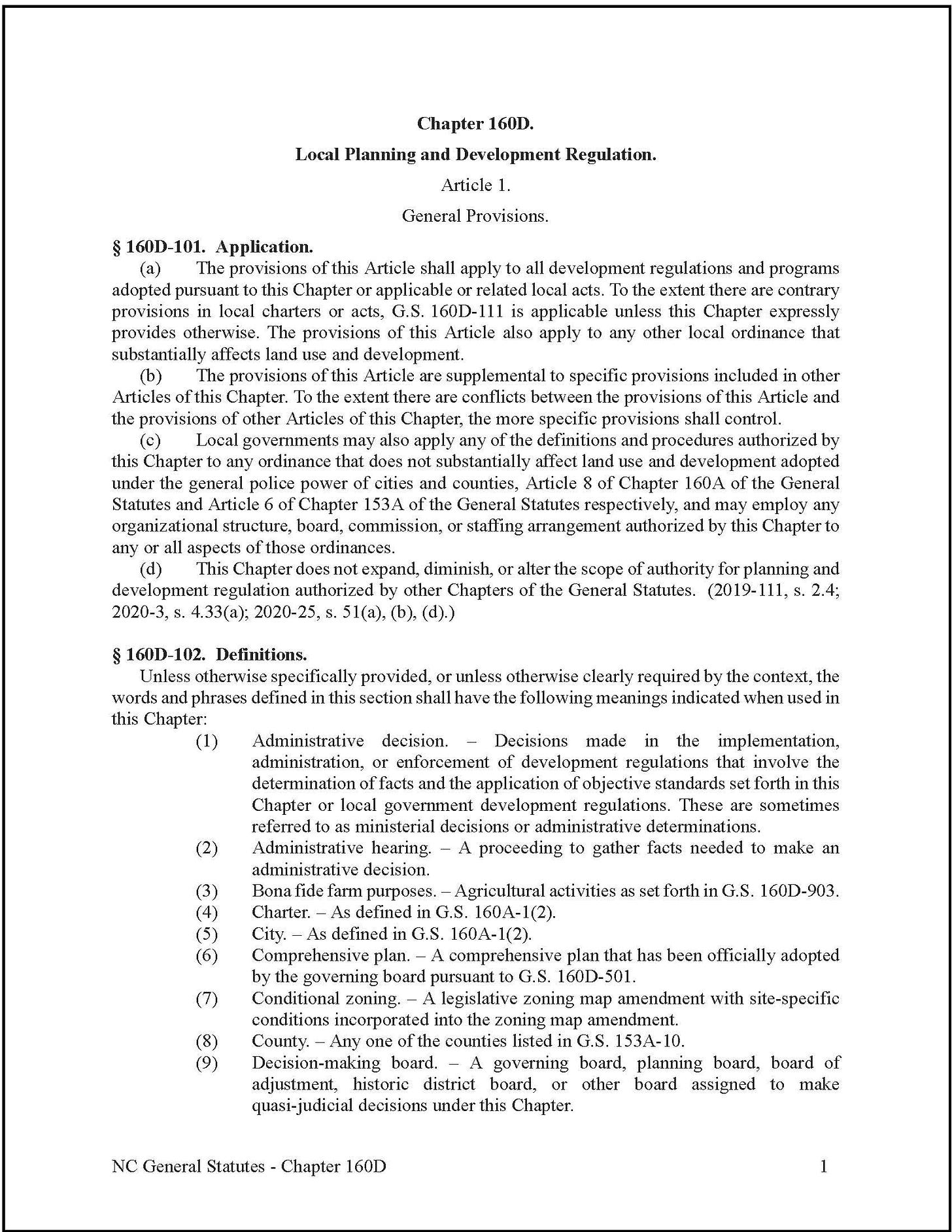

Holly Springs, NC, Dec. 27, 2025 — Chapter 160D (document) of North Carolina law governs how cities and counties regulate land use and development. While Chapter 160A defines municipalities and how they function, Chapter 160D outlines how local governments may plan for growth, regulate development, and make decisions about property use.

In practical terms, this is the law behind zoning maps, unified development ordinances, site plans, subdivisions, special use permits, variances, and development approvals. When residents attend a rezoning hearing, appeal a staff decision, or follow a controversial development proposal, they are watching Chapter 160D in action.

The chapter applies statewide and was designed to consolidate and standardize local planning and development rules that were previously scattered across multiple statutes.

What Chapter 160D does and does not do

One of the most important clarifications in Chapter 160D is what it does not do. The statute does not expand or reduce the authority that cities and counties already have under state law. Instead, it organizes, defines, and regulates how that authority is exercised in land use and development.

Local governments must still operate within the powers granted by the General Assembly. Chapter 160D outlines the structure and procedures they must follow when adopting development regulations and making decisions under those regulations.

What counts as “development”

The law defines development broadly. It includes constructing or altering buildings, grading or clearing land, subdividing property, and changing how land is used or the intensity of its use.

This broad definition matters because it determines when permits are required and when local review is triggered. Even seemingly minor activities can qualify as development under the statute, which is why residents and property owners often encounter local review requirements earlier than expected.

Development regulations and the UDO

Chapter 160D authorizes local governments to adopt a wide range of development regulations, including zoning ordinances, subdivision rules, floodplain regulations, stormwater controls, and historic preservation standards. The statute also permits consolidation of these regulations into a single Unified Development Ordinance (UDO).

Significantly, combining regulations into a UDO does not change the scope of their authority. It is an organizational tool, not a grant of new power. Each regulation included in a UDO must still be authorized by state law and applied in accordance with the procedures set out in Chapter 160D.

Legislative decisions versus administrative decisions

A key feature of Chapter 160D is the distinction between legislative decisions and administrative or quasi-judicial decisions.

Legislative decisions include adopting or amending zoning regulations and approving rezonings. These decisions are made by governing boards, typically town councils, after public notice and a legislative hearing.

Administrative decisions involve applying objective standards already in the ordinance. These decisions are often made by staff, not boards or councils. If an application meets all required standards, approval is generally required.

Quasi-judicial decisions fall in between. These include special-use permits, variances, and certain site-plan approvals. They require sworn testimony, evidence, findings of fact, and impartial decision-makers. These decisions are typically made by boards of adjustment or other designated boards, not by staff or the full council.

Understanding which category a decision falls into explains why some projects require public hearings while others do not, and why some decisions are appealable in court while others are not.

Development approvals run with the land

Another core principle in Chapter 160D is that development approvals attach to the property, not the applicant. Once issued, the rights, conditions, and obligations associated with an approval transfer to future owners unless the law provides otherwise.

This is why zoning and site approvals remain in effect when property is sold and why conditions imposed during approval continue to bind future development.

Vested rights and permit timing

The statute provides detailed rules for vested rights, which protect landowners from having the rules change mid-process after they have made significant investments.

Once specific permits are issued or site-specific plans are approved, later changes to development regulations generally cannot be applied to that project. Chapter 160D sets time limits, conditions, and exceptions for vesting and explains how vested rights can be established, maintained, or lost.

These provisions are intended to balance fairness to property owners with the public interest in regulating development.

Moratoria and limits on pause powers

Chapter 160D also allows local governments to impose temporary development moratoria, but only under defined conditions. Moratoria must be justified, time-limited, and adopted after public notice and hearings, except in cases involving immediate threats to public health or safety.

The statute also lists categories of projects that may be exempt and provides for expedited court review. This ensures moratoria are used as planning tools, not as indefinite delays.

Boards, staff, and conflicts of interest

The chapter outlines how planning boards, boards of adjustment, historic preservation commissions, and other advisory or decision-making bodies are established and operate. It also establishes rules for staff authority, appeals, recordkeeping, and public access.

Conflict-of-interest provisions prohibit officials, board members, and staff from participating in decisions in which they have a direct financial interest or a close personal relationship. For quasi-judicial decisions, the statute emphasizes impartiality and due process.

Where development rules apply

Chapter 160D also governs where cities and counties may exercise development authority, including extraterritorial jurisdiction outside town limits. It sets population-based limits, notice requirements, representation rules for affected residents, and procedures for transferring jurisdiction between local governments.

This framework explains why some properties outside town limits are subject to town zoning rules, and the county regulates others.

What this means for residents

For residents, Chapter 160D explains why local development decisions follow structured, sometimes formal processes. It is the reason public hearings are required in some cases but not others, why staff approvals cannot be overridden informally, and why courts play a role in certain disputes.

The law is designed to make land-use decisions predictable, transparent, and legally defensible. While it can feel technical or slow, the structure exists to protect property rights, ensure fairness, and limit arbitrary decision-making.

The bigger picture

Chapter 160D is the operating manual for planning and development regulation in North Carolina. It works alongside Chapter 160A to define not only what towns and counties may do, but how they must do it when growth, land use, and development are involved.

For anyone seeking to understand zoning, rezonings, development approvals, or why local government processes look the way they do, this statute is where the rules are set.