Residents, Developer Hold Noise Discussion That Escalates Into Wide-Ranging Debate on Proposed Data Center in Apex (NC)

A meeting on potential noise quickly broadened into concerns over water use, power demand, wildlife impacts, and trust in how Apex is handling the proposed data center.

Apex, NC, Nov. 12, 2025 — A resident/developer meeting billed as a chance to hear about noise from a proposed 300-megawatt data center near Old US-1 and Sharon Harris Road quickly turned into something much broader last night, a contentious ninety-minute conversation over water, power bills, wildlife, growth, and trust in local government.

Project At a Glance

Project: New Hill Digital Campus (proposed data-center complex)

Developer: Natelli Group (applicant)

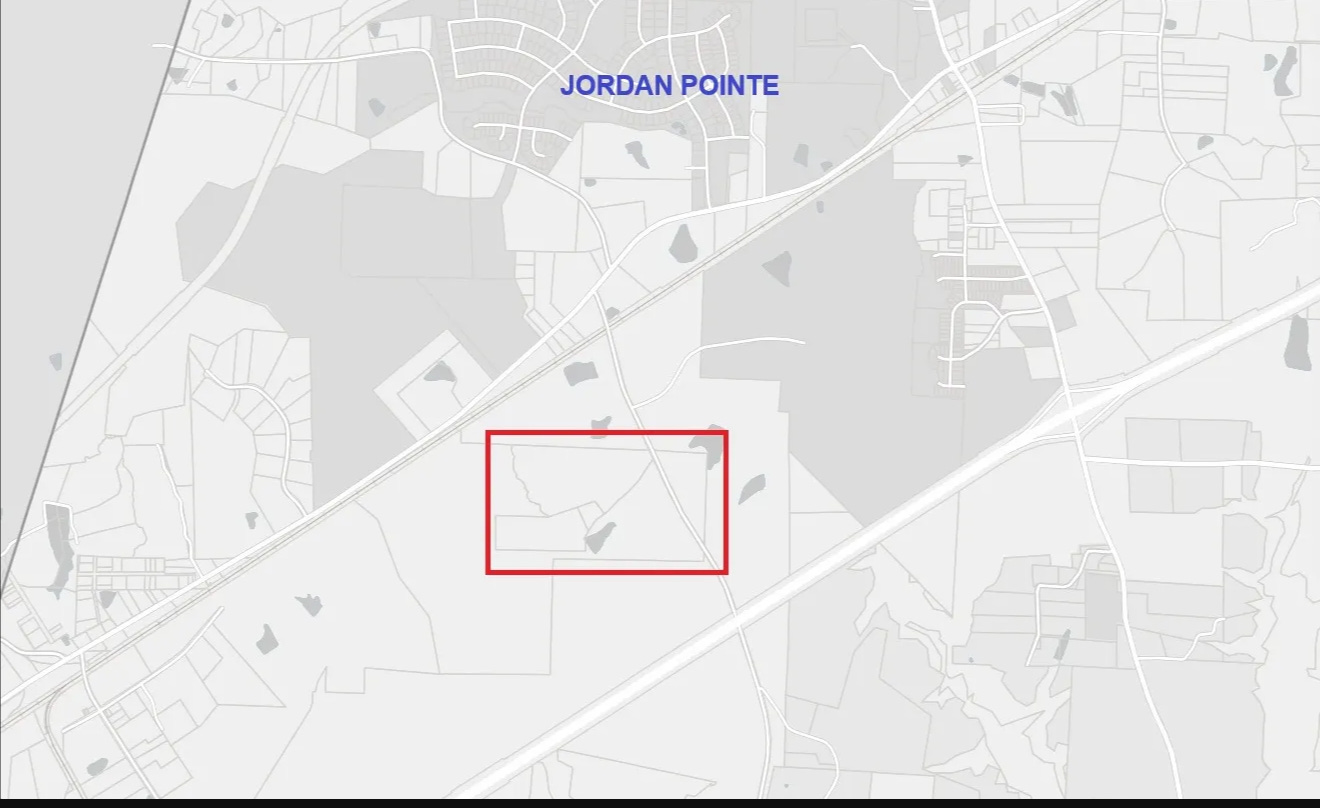

Size: ≈ 189 acres, west of Apex near Friendship Road and U.S. 64

Current Status: Rezoning & UDO amendment pending, no vote expected before spring 2026

Public Opposition: Led by Protect Wake County Coalition and residents of Jordan Manors, Charleston Village, and neighboring communities

Developers Michael Natelli (profile) and Tommy Natelli (profile), along with members of their team, including Kraig Walsleben (profile), Principal at Rodgers Consulting, a firm specializing in land and site development, and sound consultant Jeff Szymanski (profile), Senior Managing Consultant in Acoustics at Ramboll, came prepared to walk neighbors through technical details and answer questions. They left with a long list of new questions they promised to answer.

Ramboll, a global engineering and environmental consulting firm, specializes in complex industrial and infrastructure projects. Its dedicated acoustics team routinely measures, models, and evaluates noise for facilities such as data centers, with findings frequently relied upon by developers and governments to determine compliance with noise standards and design mitigation. That expertise was central to why the firm was brought to this meeting, and central to why residents had so many pointed, technical questions waiting for them.

Residents, many of whom first learned of the proposal last summer, filled the New Hill Community Center in Apex well beyond capacity, with 100-plus people crowding the small venue and standing along the walls for lack of seating. Several of the most active opponents are now working together under the Protect Wake County Coalition (www.protectwakecounty.org), which helped mobilize neighbors and drive the turnout.

A “noise” meeting that was never just about noise

From the start, the developers worked to frame the evening around sound.

Szymanski described how his team conducts 48-hour baseline sound measurements, builds a 3-D acoustical model of the proposed campus, and then layers in conservative assumptions, every home treated as downwind from the site, temperature inversions that favor long-distance propagation, and all cooling equipment running in “worst-case” mode.

He explained the basics of decibels (sound levels), stating that a 3-decibel increase is barely perceptible to most people, while a 5–6 decibel increase is noticeable. Ramboll’s goal, he said, is to keep the project’s noise contribution within that 3–5 decibel change at noise-sensitive locations.

But neighbors wanted more than methodology. They pressed for specifics:

Exact dates and locations of recent sound measurements.

How transient noises, including helicopters, are filtered from the data.

Whether the model reflects prevailing southwest winds and temperature inversions.

How the team will handle low-frequency tonal hum, a common complaint near large fan systems.

Szymanski distinguished between ground-borne vibration (minimal for data centers because equipment is vibration-isolated to protect sensitive electronics) and airborne tonal noise, which is more noticeable to neighbors and can be controlled through engineering.

The conversation quickly shifted from acoustics to policy: not just how noise is modeled, but what limits the project will have to meet, and where those limits will apply.

Building an ordinance as they go

Unlike many cities with defined decibel caps, Apex’s noise ordinance is rooted in subjective “reasonableness.” That vacuum has become a central friction point.

Town staff, working with the developer, have floated a 60 dBA (A-weighted decibels) property-line limit in draft UDO changes. The developer said recent discussions have centered on 55 dBA at the property line, though nothing is final.

Residents pressed hard:

Where the limit is measured: Property line vs. the nearest homes and schools.

How noise is weighted: Whether Apex should also measure low-frequency rumble using C-weighting. (Learn: Understanding frequency ratings)

How compliance will be verified: Especially after construction.

Szymanski noted that C-weighted limits are rare in local ordinances nationally but said he would need to “get back” with a specific recommendation.

Developers outlined a two-stage verification process: a pre-construction study to set targets and a post-construction study to test real-world conditions. If noise exceeds limits, additional mitigation will be needed. When residents asked for examples of post-construction verification at similar data centers, the team acknowledged that their most significant comparable projects are still under construction.

“Industrial corridor” vs. “this wasn’t what we were promised”

One of the night’s core disputes was whether a hyperscale data center is compatible with Apex’s long-term land-use plans:

Developers’ view

Apex’s comprehensive plan designates the corridor as industrial.

The existing zoning allows light industrial, which they describe as the most intensive applicable category.

Other uses, such as manufacturing, distribution, and recycling, could arrive today with fewer controls than the data center is agreeing to.

The data center aligns with the town's vision for the area.

Residents’ view

The industrial label never implied a 300-MW hyperscale data center, one larger than the entire town’s electric load.

Prior planning fights, including the nearby water-treatment-plant controversy, left residents skeptical of assurances that “nothing is a done deal.”

Many feel decisions are presented as open for input long after substantive choices have been made.

One resident captured the tension bluntly:

“How many signatures would it take for you to ditch this project?”

The developer did not offer a number.

Wildlife, water, chemicals, and air: “It’s not just about our ears”

Although the meeting focused on noise, residents repeatedly pivoted to broader environmental concerns:

Wildlife impacts

Residents asked how continuous, low-frequency sound might affect birds, deer, pets, and other wildlife in the surrounding wooded areas. Szymanski said this falls under biological specialists; the development team said they would consider wildlife concerns as they refine noise-mitigation measures.

Water usage and “polishing”

Developers said the data center would use about half a million gallons per day of reclaimed water during peak heat, with roughly one-third evaporated in cooling and two-thirds returned to the wastewater plant. They emphasized:

The facility is not drawing from the potable supply.

Reclaimed water must be “polished” (further treated) on-site before use to protect sensitive cooling equipment.

Residents challenged the framing:

Cary uses reclaimed water for irrigation, contradicting claims that the water has no other uses.

Evaporated water could contain additives, raising concerns about air quality.

They requested graphs showing water usage by temperature and humidity, noting the long, warm seasons in Apex.

Developers said such data “likely exists,” but they did not have ready access to it.

Power, bills, and who pays for upgrades

The developer has requested 300 MW of transmission service from Duke Energy, roughly triple the entire town’s current load.

Developers argued:

The project connects to Duke’s transmission system, not Apex’s distribution network.

The developer will pay for all project-specific grid upgrades.

Retail electric rates rise due to regional supply-demand patterns, not a single facility.

Data centers generate significant property tax revenue without increasing school enrollment.

Residents countered:

Data center growth in Maryland and Virginia coincided with steep increases in electricity bills.

Even transmission-connected facilities place new demands on the regional grid.

No one has provided any billing protections or caps.

Traffic, light, and annexation

Walsleben said the project is expected to employ 200–250 workers across three shifts. Primary access would be from Old US-1, with a controlled/emergency entrance on Sharon Harris Road. Lighting, he said, will be fully shielded to prevent spillover at property lines.

Regarding annexation, the team said the site lies within an area Apex plans to incorporate, and that annexation would allow more efficient alignment with reclaimed-water infrastructure.

Residents, however, connected annexation questions to broader worries about rapid growth, cumulative environmental impacts, and lingering distrust in the town’s development process.

Trust and process: “We’re not being heard”

Distrust permeated the meeting.

Residents cited:

Low-notice early meetings.

A one-directional Environmental Advisory Board session.

Unanswered written questions from prior meetings.

Maps that fail to show surrounding neighborhoods and wildlife areas.

When asked when answers to the growing list of questions would be provided, the developer said that the list is long and complex and that responses will come “as we are able,” without offering a timeline.

Where things stand: far apart, with many questions still unanswered

As the meeting wrapped up, both sides’ positions were clear:

Developers maintain:

The location is appropriate under Apex’s land-use plan.

They are willing to abide by new, project-specific sound limits stricter than existing Apex rules (when agreed upon and final).

They will fund all required grid upgrades and implement extensive mitigation measures.

The project will generate significant tax revenue without burdening schools.

Residents argue:

The project is too large, too industrial, and too close to homes and wildlife.

Noise is only one concern; water, air, wildlife, power bills, and cumulative impacts matter just as much.

Apex’s planning history demands stronger guarantees and greater transparency.

Many technical questions remain unresolved.

Unanswered questions include:

Whether Apex will adopt A-weighted, C-weighted, or dual noise limits, and at what levels.

Actual modeling results for homes, schools, and wildlife areas.

Details of comparable data centers developed by the team.

A clear explanation of polishing and associated chemicals.

Water-use projections tied to climate conditions.

Wildlife-impact assessments.

Any mechanism to insulate residents from potential grid-related rate impacts.

What began as a noise meeting made one thing clear: noise is only the beginning of the debate.

The developers say they will return with more information and in a larger room. The residents made equally clear: they will return, too.

Holly Springs Update Coverage & Apex Town Council Timeline

Earlier Holly Springs Update Coverage

November 3, 2025 - Apex (NC) Residents Speak Out at Council Meeting to Oppose Proposed Data Center; Officials Outline Long Review Timeline

October 28, 2025 - Protect Wake County (NC) Coalition Meeting Rallies Over 100 Residents to Oppose Proposed Apex Data Center

August 27, 2025 - Proposed Data Center Near Shearon Harris Plant in Apex Spurs Debate Over Annexation, Rezoning, and Neighborhood Impacts

Next Steps: Apex Town Council Timeline

Nov. 20th: Technical Review Committee meeting.

Jan. 22nd, 2026: Joint Council/Planning Board work session (no public comment).

February 2026: Second neighborhood meeting.

March 2026: Earliest potential public hearing before the Planning Board and Town Council.

Note: Town officials have said updates will continue to be posted on the municipal website and shared through the Ask Apex portal.

I’ve never heard about this developer. Very concerned about water usage. Seems like this construction is not very environmental friendly. They have to disclose their PUE and WUE parameters for this data center.

Great work, well written. I wonder if #natellicommunities understands their use of the word "consider" vs will. Because we know, don't we? #nodatacenterApex

Are three of them holding their hands the same way on purpose? Hehe.